Inference engines

If you are working with local LLMs and optimising GPU usage, latency, costs, etc. for production, you have to use an inference engine. They will help you get optimal performance.

Recognizing the need, many inference engines have added native support for structured LLM outputs. Some of them use the constrained decoding backends we discussed earlier, while others have tried to implement constrained decoding on their own.

High throughput: SGLang and vLLM

Both SGLang and vLLM originated from the LMSYS org, and represent the current state-of-the-art in inference engines. Both support XGrammar, llguidance, Outlines-core.

vLLM is currently the most popular and versatile inference engine. It focuses on maximizing the GPU utilization, and is really great at batching tasks. It also implements a lot of other optimizations to reduce latency and costs.

SGLang is built on top of vLLM. It reuses a lot of vLLM's architecture, and adds some more optimizations on top of it specifically for structured outputs:

- Super-fast stateful generation in interleaved flows, i.e. prompt → output → prompt → output..., using a caching mechanism called RadixAttention, that caches LLM state from previous outputs.

- Compiler-level optimizations on top of constrained decoding backends to lower latency further.

- High-level DSL to make it easy to define complex schemas and interleaved flows.

- Lots of caching.

- Better integration with multimodal LLMs.

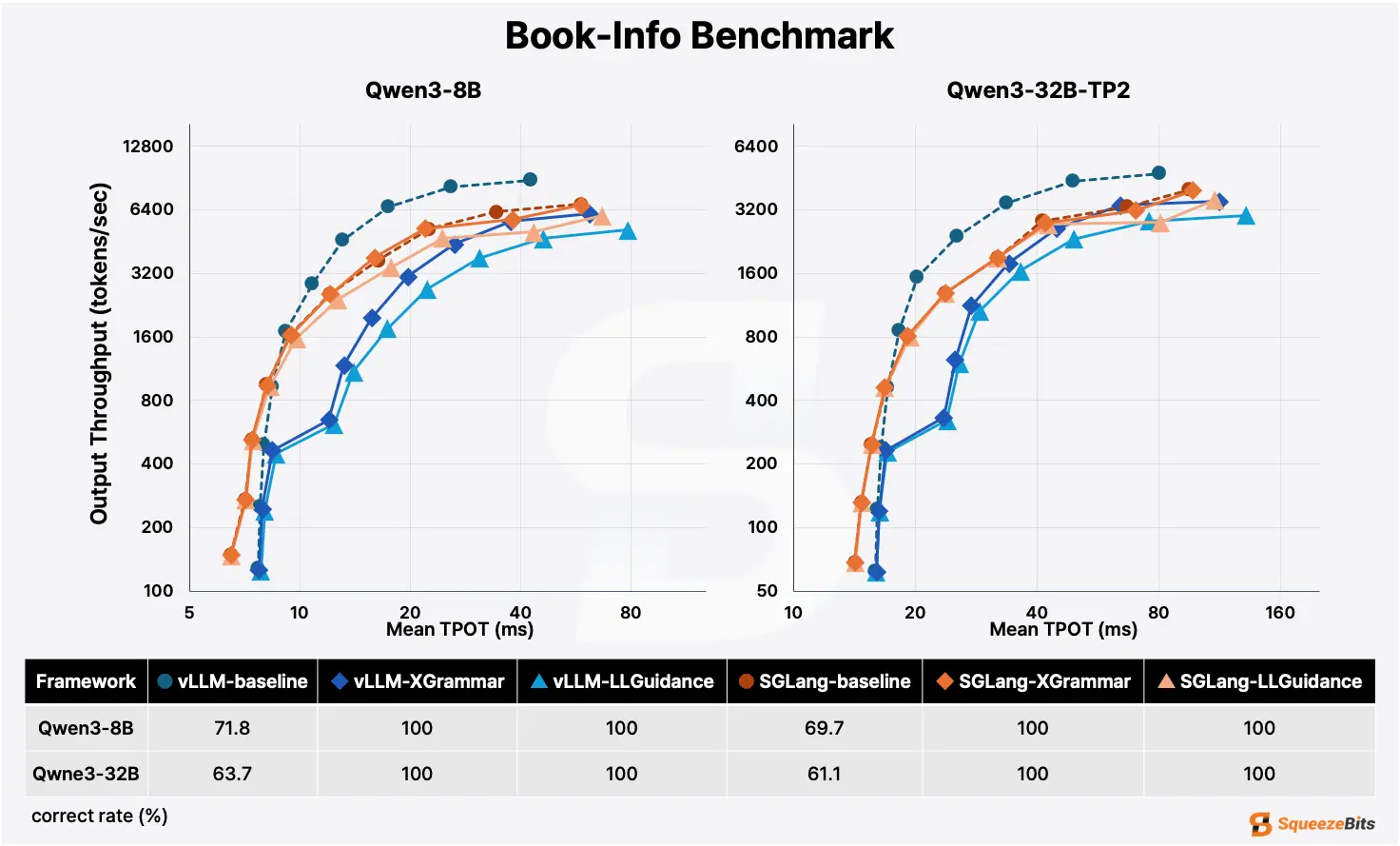

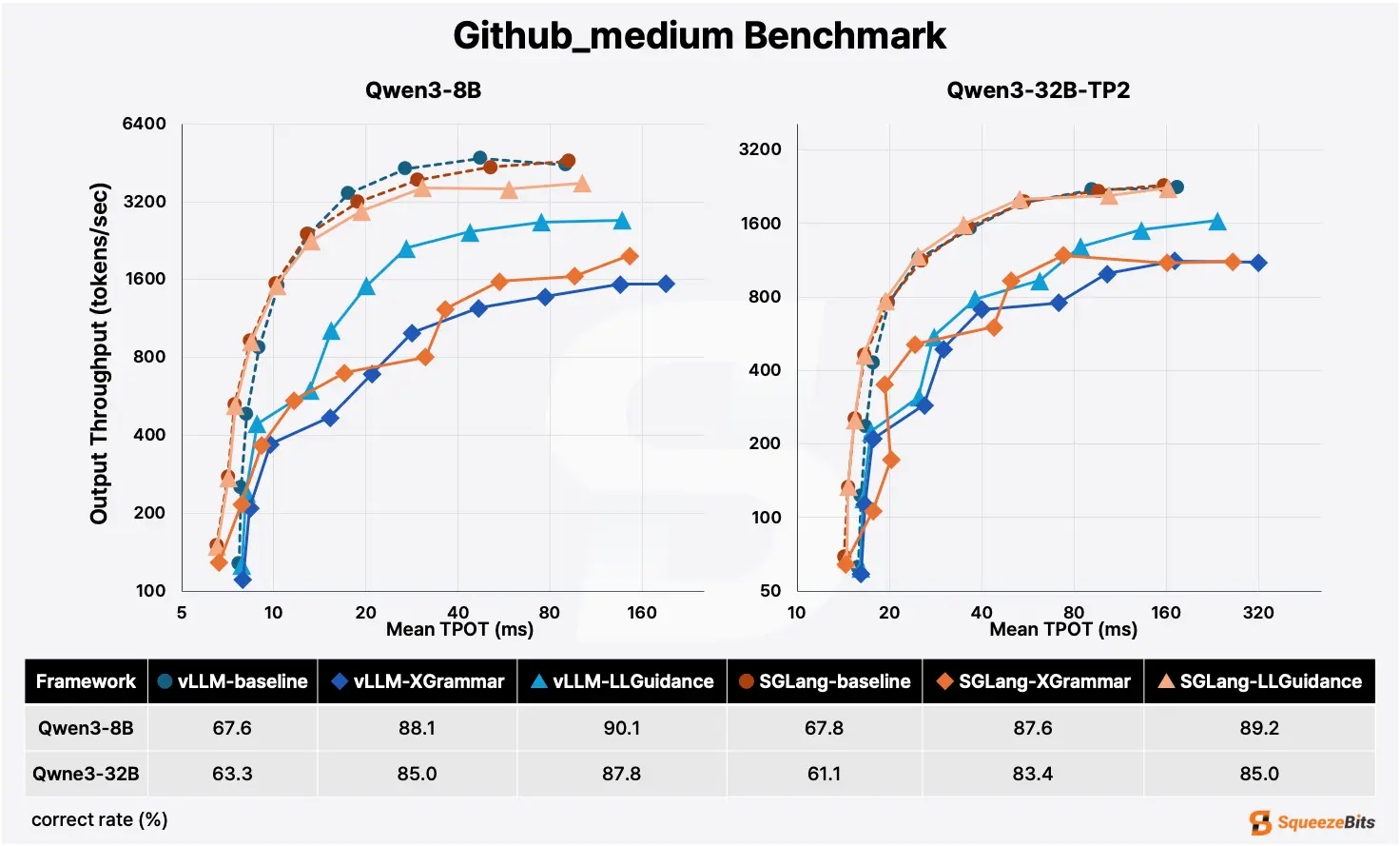

SGLang mostly outperforms vLLM on structured tasks.

But there is one major exception: structured tasks with very low cache hit rates. We'll show what we mean using two examples:

-

You serve 100+ concurrent users. Every user request has a unique prompt and schema. Before SGLang generates a single token, it queries its cache: "Have I seen these prompts and schemas before? Can I reuse any part of my cache?". Since requests are unique, it finds nothing, and the time spent traversing the cache is wasted. vLLM's scheduler is simpler, it batches these requests and starts generating tokens immediately.

-

The static part of your prompt (the instructions) is tiny compared to the dynamic part (the user data), and the dynamic part never has repeat tokens. For example, a summarization tool where one prompt is "Summarize this article: [Unique Article Text 5k tokens]", and the other prompt is "Summarize this article: [Different Article Text 5k tokens]". SGLang caches every unique document in memory, hoping it will be seen again. When memory fills up, SGLang wastes massive compute constantly deleting old cache nodes to make room for new ones. This is called cache thrashing. vLLM's memory is designed specifically for this kind of "high churn". It doesn't hope for reuse, and is fast at freeing memory blocks.

For these kind of tasks specifically, where the cache hit rate is very low, vLLM is the better choice. For everything else, SGLang takes the lead.

Note that document extraction tasks run on the same kind of documents (invoices, bank statements) don't suffer from low cache hit rates, because these documents are similar in terms of layout, text, fields, line items, etc.

Legacy: Hugging face TGI

Hugging face TGI was the standard inference engine before vLLM and SGLang took over. It is stable, easy to deploy, license compliant (Hugging Face ecosystem integration), fails gracefully, and has the most mature Docker containers.

For structured outputs, TGI integrates Outlines-core, and thus does not support large/infinite schemas and very high-throughput needs. But if your traffic is low-to-medium, TGI is sufficient.

Local hardware, cheap cloud instances: Ollama and llama.cpp

Ollama and llama.cpp are great for prototyping, POCs, one-time tasks, internal tools, etc. when you work with limited hardware and don't need to scale at all. You can use them on local hardware or cheap cloud instances.

llama.cpp is a C++ inference engine, optimized for local hardware like Apple Silicon, CPUs, consumer GPUs, phones, even Raspberry Pis. It runs without heavy dependencies, and prioritizes low-resource efficiency and "batch size 1" performance. It uses its own constrained decoding backend that accepts GBNF grammar inputs.

Beware, llama.cpp uses GBNF grammar inputs that are somewhat painful to write and debug, and you also need to manually manage models in GGUF files which is cumbersome.

Ollama is a wrapper over llama.cpp. It abstracts away the complex build flags, model weight management, GGUF handling, etc. that make working with llama.cpp difficult, and in fact provides the most developer-friendly experience out of all the inference engines listed on this page.

Ollama supports template imputs for JSON, XML, etc.. It converts them into GBNF under-the-hood and passes them to the underlying llama.cpp constrained decoding backend.

For structured outputs, Ollama is the easiest entry point.

Both llama.cpp and Ollama are unique because they aren't strictly optimized for massive NVIDIA GPU clusters like vLLM, SGLang, and the others. Instead, they prioritize:

-

Universal Compatibility: They run on everything. CPUs, Apple Silicon, and consumer GPUs.

-

Quantization: Under-the-hood, they support the quantization technique, which makes it possible to run 70B parameter models on a single MacBook Pro with minimal quality loss.

-

Low-Resource Efficiency: They have very low overhead for "batch size 1".

However, they will choke on concurrent users and high-throughput tasks.

Edge devices, browsers: MLC-LLM

The MLC-LLM inference engine compiles models and constrained decoding logic into native libraries (e.g., .so, .dll, .wasm). It is the standard inference engine for structured LLM outputs on edge devices (iOS/Android), with support for XGrammar as the constrained decoding backend. It significantly outperforms llama.cpp on mobile GPUs (e.g., on an iPhone 15 Pro).

Its sibling project, WebLLM, enables high-performance structured outputs entirely inside a web browser. This eliminates backend server costs by running the LLM client-side.

Note that you can only use MLC-LLM and WebLLM with models that the MLC team have explicitly built support for (Llama, Mistral, Gemma).

Pure C++ inference: LMDeploy

LMDeploy is a pure C++ inference engine, unlike vLLM and SGLang. It is the only engine that matches (and sometimes exceeds) SGLang’s throughput, particularly on NVIDIA architectures where it is built to aggressively optimize throughput. It appears to be implemeting its own constrained decoding backend, but we are not sure.

It works well for generic high-throughput structured tasks, but lacks the extensive rich features offered by vLLM and SGLang. Also note that its Python API is an extremely thin wrapper around the C++ core, and debugging issues means diving into C++ stack traces.

Build your own inference engine: TensorRT-LLM (TRT-LLM)

TensorRT-LLM is NVIDIA’s official toolkit for building your own inference engine. This takes time (minutes to hours), disk space, expertise. They recently integrated XGrammar into the toolkit.

Only specific kinds of users need to consider TensorRT-LLM:

-

If you have selected a single model (e.g., Llama-3-70B), fine-tuned it, and plan to serve exactly that version for months. You often get 20–40% higher throughput than vLLM/SGLang on the same hardware.

-

If you team already uses NVIDIA Triton Inference Server for non-LLM models (OCR models, recommender systems, etc.), TensorRT-LLM can integrate easily. For example, you can chain a vision model (TensorRT) feeding into an LLM (TensorRT-LLM) entirely within GPU memory, without the data ever round-tripping to Python code.

-

It is written by the same people who designed the H100 chips. If you are paying for those expensive H100 clusters, TensorRT-LLM ensures you are getting maximum performance possible. vLLM also promises this to an extent, but it can sometimes fall back to less optimized runtimes when used with certain LLMs.

-

Like llama.cpp, TensorRT-LLM supports quantization, but for heavier LLMs. This allows you to run LLMs on less capable, on-premise client hardware which wouldn't be otherwise possible.

No inference engine : transformers

For offline use, or online single-user scripts, you can run "raw" inference using the model loader via Hugging Face transformers, without any inference engine. This basically just loads the model into matrices and runs the math (matrix multiplication). It doesn't optimize for speed or throughput at all. You can enforce structured output by:

- using Outlines and Guidance libraries (wrapper libraries over outlines-core and llguidance respectively, discussed next) that sit on top of Hugging Face transformers to do this for you.

- manually manipulating the probability scores for the output token, directly in Python.

Executable Inference engine : MAX

MAX (by Modular) is a new inference engine that takes a fundamentally different approach. Standard inference engines (like vLLM) write Python kernels to perform LLM inference on GPU. This interaction between the kernels and GPU creates tiny delays.

MAX compiles the entire end-to-end LLM inference pipeline into a single native executable, and removes removes the Python kernel overhead entirely, offering extremely high throughput. For structured outputs, it utilizes the llguidance backend.

Note that Max cannot read a .safetensors file directly. Before you can run the LLM, you have to use a tool provided by Modular to convert the LLM into Max’s internal format. This adds friction to the development cycle. Also, if a new LLM comes out tomorrow, Max will not run it until the Modular team updates their conversion tool to support Llama-4.

Scale naturally

You do not need to marry one inference engine forever. Most teams scale in phases:

-

Start with Ollama for local prototyping, internal tools, POCs. It is simple and private, but it cannot handle concurrency or batching.

-

Next, move to high-performance runtimes like SGLang, vLLM, etc. You gain batching and cache optimizations, but you lose simplicity and ease of use.

-

Finally, adopt a distributed platform. When you need to span multiple clusters or regions, these platforms handle the infrastructure overhead (autoscaling, observability, etc.).